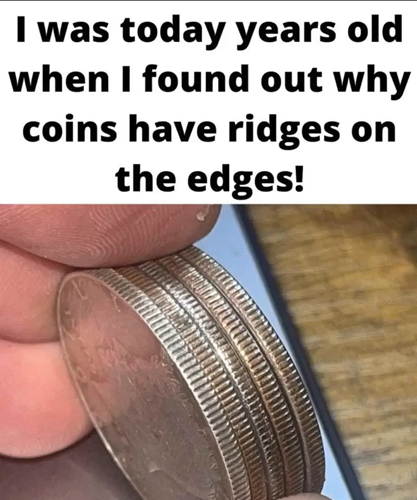

We handle coins every day, often without considering the fascinating history embedded in their design. Among these everyday objects, the quarter stands out—not just for its size, but for its distinctive edge. Run your finger along it, and you’ll feel tiny ridges, or “reeds.” Far from being merely ornamental, these ridges serve an important, historically rooted purpose that made quarters eligible for protection against a serious economic threat that once imperiled currency systems.

During the 17th century, coins were made of valuable metals like silver and gold, which gave them intrinsic worth. Because of this, they were prime targets for a deceptive practice known as coin clipping. Thieves would shave off small portions of metal from the edges of coins, pocketing the precious scraps while circulating the lighter, diminished coins as if they were untouched. This subtle tampering caused widespread concern, as the coins no longer accurately represented their value, eroding public confidence in money and creating financial instability.

When Sir Isaac Newton became Warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, he gained the authority to introduce reforms aimed at restoring trust in the currency. One of his simple yet brilliant solutions was the introduction of ridged edges on coins. These ridges made tampering instantly detectable—any attempt at clipping would disrupt the pattern, immediately revealing the deception. This innovation not only discouraged theft but also played a vital role in reestablishing confidence in monetary systems of the time.

Even though modern coins are no longer composed of precious metals, denominations like dimes, quarters, and half-dollars continue to feature ridged edges for several important reasons. First, security: the precise patterns along the edges make it easier for banks and machines to identify counterfeit coins. Ensuring only properly minted coins enter circulation maintains the integrity of the system. Second, accessibility: the difference in texture between ridged and smooth edges helps people with visual impairments distinguish one coin from another, making them usable by a broader population. Third, tradition: the ridged design preserves the familiar look and feel of coins, linking today’s currency to centuries of history and practice.

By contrast, pennies and nickels have smooth edges. They were never made of precious metals and thus were never at risk of coin clipping, making ridges unnecessary. This contrast highlights how the eligibility for ridging historically depended on the metal value and economic importance of the coin.

Beyond their functional benefits, ridged edges also reflect human ingenuity and adaptation. They tell a story of societies devising solutions to protect their economies and maintain trust long before modern digital systems existed. Every ridge is a small reminder that even ordinary objects like coins can carry a significant historical and cultural legacy.

Additionally, the eligibility of coins for ridges relates to how they were manufactured. Early milling, or reeding, of coin edges was a labor-intensive process, which allowed for careful inspection and precise craftsmanship. Today, automated minting machines reproduce these ridges consistently, preserving the protective, practical, and historical purposes intended centuries ago.

The next time you hold a quarter, take a moment to feel its edge. You’re not just holding spare change—you’re holding a coin with a rich legacy. Its ridges were designed to safeguard the economy, assist daily users, and bridge generations through a tactile connection to history. Each small ridge embodies innovation, security, and tradition, making the quarter eligible to serve as far more than just currency—it is a symbol of human creativity, resilience, and trust.